December 18, 2025 marks 2 years since OpenMadoola's initial release (and 39 years since The Wing of Madoola released). I thought it would be fun to go over what's been added to OpenMadoola in 2025. Because I haven't done one of these for previous years, here's a brief summary of the work that's been done so far:

Now let's move onto the (relatively) major changes from 2025:

I thought it would be nice if OpenMadoola had an icon so it would look more like a real desktop program. Thankfully (because I'm a terrible artist) Kak offered to draw an icon for me. He had to do it in a bunch of different sizes and crops due to what different operating systems expect. On my computer, here's what the game looks like on the desktop:

And here's what it looks like in the system menu:

If you're interested, here's an uncropped version of the largest 512x512 size. I think Kak did a fantastic job!

OpenMadoola is pretty easy to build, but I wanted a way to distribute binaries to Linux users who prefer to use prebuilt software. The best way to do this seemed to be creating a Flatpak package for OpenMadoola and distributing it on Flathub. Most Linux distributions either come with out of the box support for Flathub, or can have it added by installing a package or two.

Essentially the way Flatpak packages work is that they all link to a common set of libraries, the Freedesktop SDK. This collection gets centrally maintained and updated, but will remain ABI stable (meaning compiled binaries will continue to work unmodified) through its two-year support duration. A new version of the SDK is created once a year. Each Flatpak package only provides its own binaries/data and any libraries it uses that aren't in the common collection. There's also KDE/GNOME runtimes that are built on top of the Freedesktop runtime for Qt or GTK software respectively. Flatpaks are run inside a container and have a statically set list of permissions. Flatpaks distributed on Flathub get manually reviewed during the initial submission process, and are built from source without internet access on Flathub infrastructure, meaning you know the compiled binary on Flathub matches the source code.

Overall Flatpaks are pretty nice from a user perspective. You can install a package from your desktop environment's package manager GUI in one click, it'll run on your system without having to fuss around with compiling or making sure the correct libraries are installed, and it gets updated automatically. The Steam Deck supports Flathub out of the box, so this also makes it easy to run OpenMadoola there.

I was able to reduce sound latency by 2 frames by making the way the game generates audio smarter. In case you're unfamiliar with how audio works on computers, it's basically like this:

The new system has a target of 1024 samples (~1.4 frames). If there's more than that many samples queued, the game will skip generating any audio. Otherwise, it will generate a frame's worth of samples. After this, if there's less than 1024 samples queued, the game will generate another frame's worth of samples. This keeps sound latency between 1 and 2 frames, without skipping on any computer I've tested it on. I won't post a video because it's not really noticeable from watching a recording, but when you play the game it feels much nicer with the shorter audio latency. At this point, I think playing OpenMadoola on a computer feels similar to playing The Wing of Madoola on real NES hardware connected to a LCD TV in game mode using a high-quality upscaler (OSSC or Retrotink or something). It's not quite as snappy as playing on a CRT (I don't think that's possible on a conventional desktop OS), but it's almost there and it feels much better than playing in an emulator.

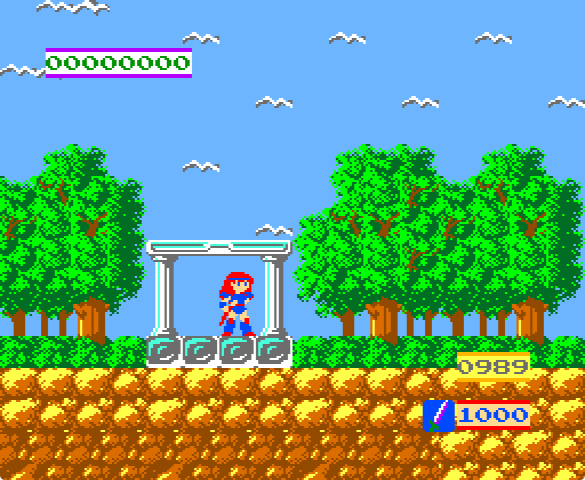

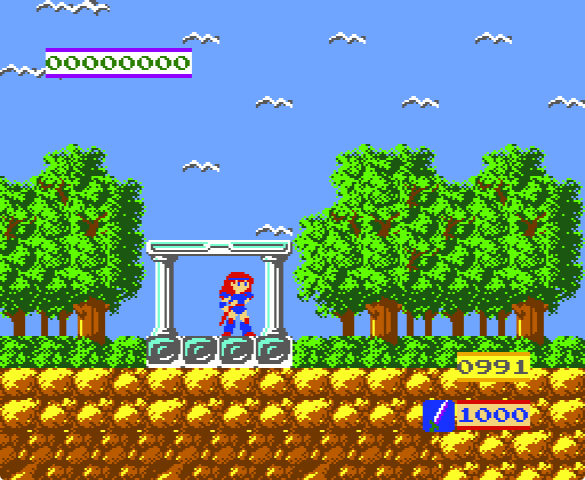

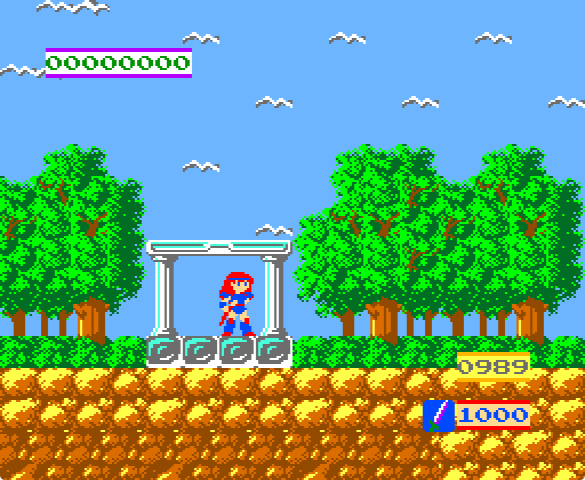

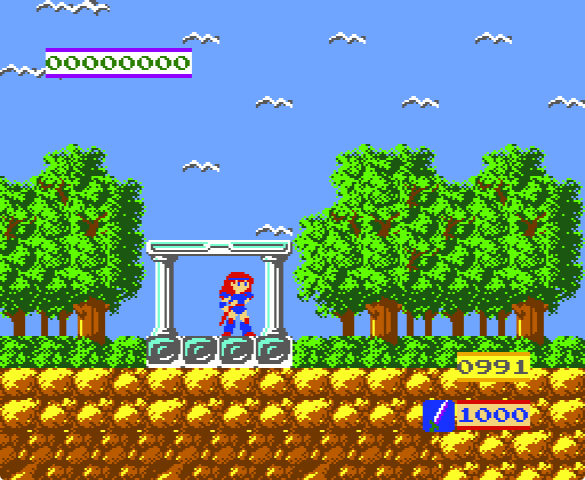

After I added arcade mode, one thing that bugged me was how the colors looked. The home version of the NES outputs its video directly in composite, so when Nintendo designed the VS. System arcade board they had to make a new version of the PPU (picture processing unit) chip that could output RGB so it could be used with an arcade monitor. The colors the VS. System PPU generates are much more garish than what the home PPU generates. At some point (I think looking at the NESdev forum) I came across a theory that this was an intentional strategy to combat the limitations of the arcade monitors Nintendo used. They made the reds overly bright to counteract the weak red phosphors used in early 1980s CRTs, and they made all the colors bright/washed out because arcade monitors had a different gamma curve than modern computer monitors and TVs. I added an option to modify the color palette to try to simulate how it would look on an arcade monitor. I don't have a real VS. System cabinet to compare against, but to my eyes the results look better than directly outputting the raw RGB values.

|

|

| Raw RGB | Color corrected |

I also changed my mind on the arcade mode camera. Originally I decided to keep the camera from the NES version for arcade mode, where Lucia is locked at the center of the screen and is automatically placed 2/3 of the way down whenever she's on the floor. This was because I initially thought the arcade camera was just the NES camera except it only moves vertically when Lucia is at the edge of the screen, which seemed strictly worse. When I was going over the comparison shots on my arcade version page, I determined this isn't the case. The way it actually works is that Lucia doesn't get automatically placed vertically, and there's a 32 pixel deadzone at the center of the screen where Lucia can move without scrolling the screen. This means the arcade camera was changed as a deliberate choice to try to make the game feel less twitchy. Once I realized this, I decided to reproduce the arcade version's camera for OpenMadoola arcade mode. One interesting tidbit is that this camera works the same as the camera in Blaster Master, which was the next game by Kenji Sada, Madoola's main programmer.

SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) is a technique where you process lots of data in parallel to speed up a program. I decided that I wanted to learn about SIMD, so I decided to profile OpenMadoola to see what functions could be sped up. The function that the game spent the longest amount of time in turned out to be a utility function that applies a color palette to an 8x8 tile and writes it to the framebuffer as NES color indices. This function was an ideal candidate to be sped up with SIMD, as I could use a byte shuffle instruction to palettize the tile in bulk. I started by doing an AVX2 version. AVX2 has 256-bit registers, and OpenMadoola converts the tile data from NES planar format to 8bpp chunky at launch, so this means that I'm able to palettize a sprite in 2 shuffle operations instead of 64 palette lookups. With this optimization, the game went from spending ~21% of its time in that function to ~1.7% of its time. I also did SSSE3 (the earliest Intel SIMD ISA with a byte shuffle instruction) and ARM NEON versions. Both of those instruction sets use 128-bit registers, so they take 4 shuffle operations to palettize a sprite. AMD64 and ARM64 both support unaligned writes, so I can also write the tile to the framebuffer a row (8 bytes, or 64 bits) at a time instead of a pixel at a time.

In case you're wondering why I'm bothering to do the drawing and palettization in software instead of using a shader, it's because the only easy cross-platform way to do so is by using OpenGL, and OpenGL drivers are so bad on Windows that a program like OpenMadoola would use far more CPU and far more power drawing the graphics with OpenGL than with software rendering. I mostly don't use Windows so I don't feel like doing both a DirectX backend for Windows and an OpenGL backend for Linux and Mac OS X.

OpenMadoola doesn't do very much processing. In practice, on any reasonably modern computer these changes made the game go from using ~1.5% of the CPU to ~1.2%. However, I still had fun learning, and that's what matters the most :)

Overall I think OpenMadoola is in a pretty good place now. Most of the rough edges have been worked out, and I've taken care of all the minor stuff that bothered me. Maybe I'll do something special for The Wing of Madoola's 40th anniversary next year.